It’s been nearly a year since I moved into the new and larger office. Many people have asked about what I’m going to do with all the space upstairs and next door since it’s just me afterall. I’m thrilled to share that the practice is growing into a team of providers that bring a greater breadth of skills and specialities to better serve our community.

I’d like you to meet our first new provider, Megan Benham. Megan and I started working together while I was on my post-doctoral fellowship, and I am so happy to welcome her into our practice as a new provider offering therapy, assessments, consulting, and working with new patient intakes.

Megan is accepting new therapy clients through Presence Development Services (I’ll share more on this soon) and you can contact her at megan@bryanharrisonphd.com.

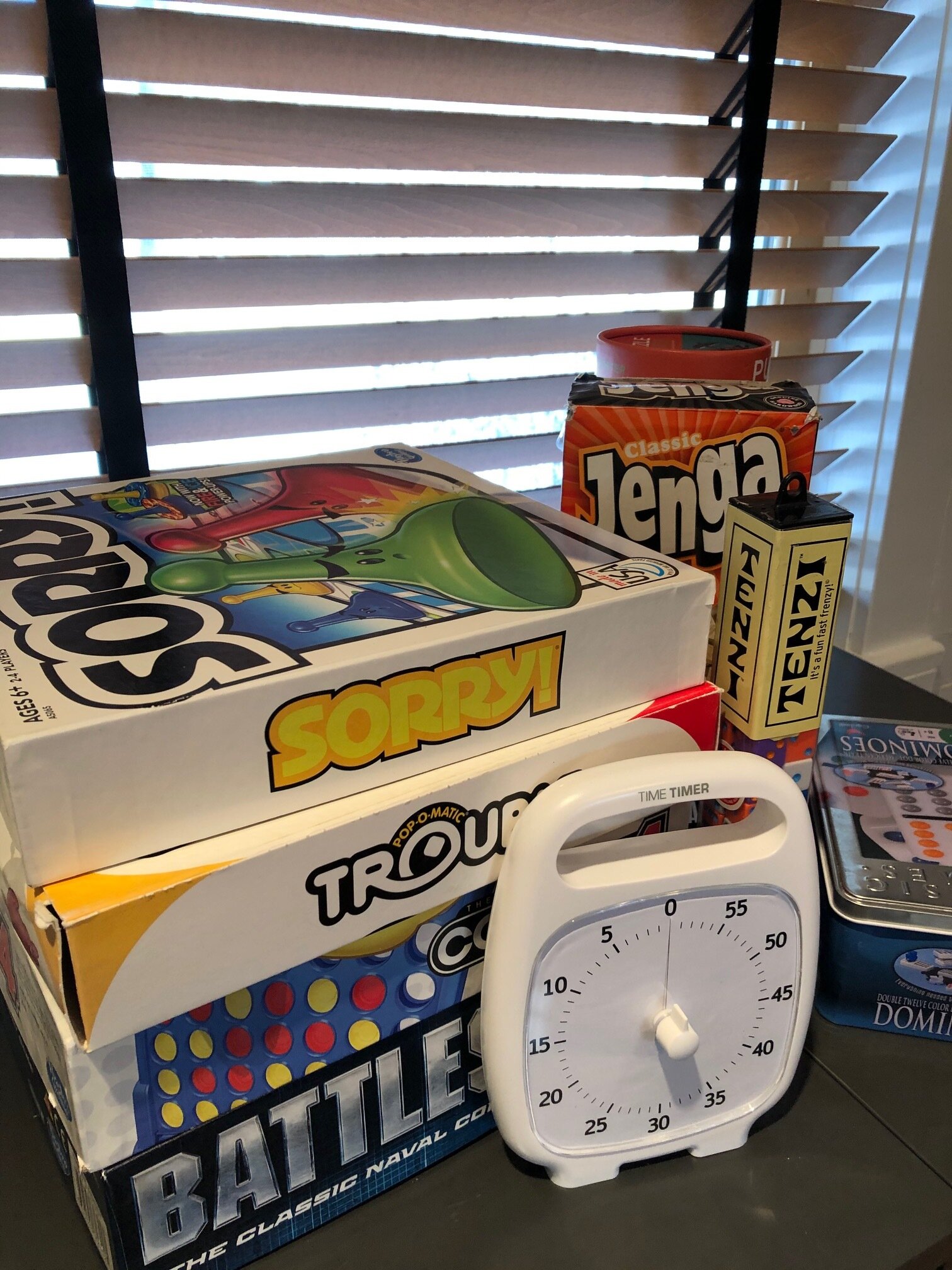

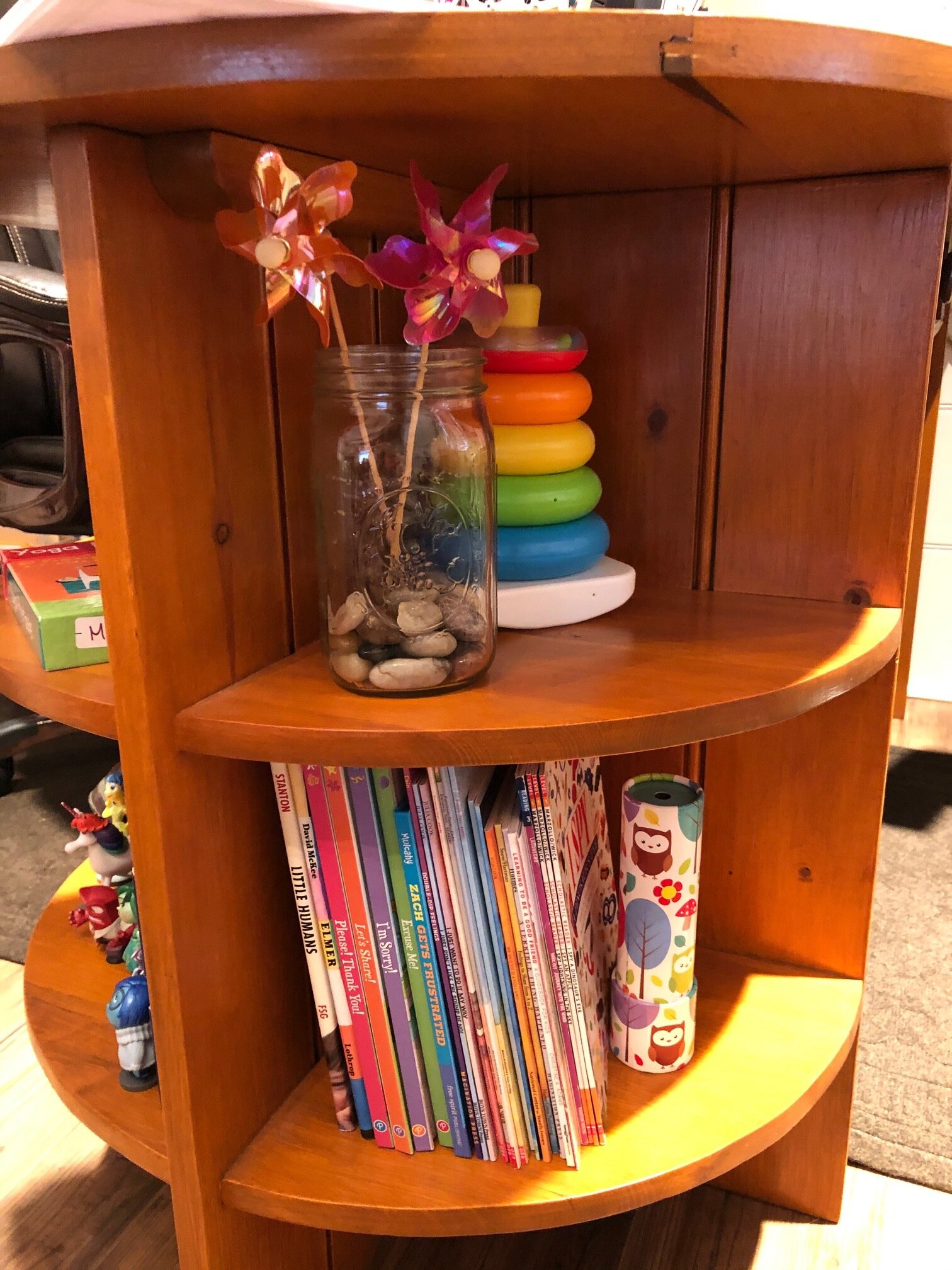

Megan works from the building we lovingly refer to as the “side office,” the stand-alone building next to the main office. She’s mixed our style with her own pops of personality (and board games!) to create a welcoming space for patients and their families.

So, in her own words, meet Megan.

I am an advanced doctoral student pursuing my Doctorate of Psychology (Psy.D.), and I am so excited to have the opportunity to become a part of Dr. Bryan Harrison's practice.

I moved to Rochester in 2007 to attend St. John Fisher College for undergraduate and quickly fell in love with Rochester. In 2011, I began my doctoral program at the University of Hartford.

After living in Connecticut while completing my coursework and beginning my clinical training, I moved back to Rochester and happened to link up with someone at Mt. Hope Family Center who put me in touch with Dr. Christie Petrenko at the Univeristy of Rochester. Dr. Petrenko took me on as a graduate student, and for the last five years I have been working with her on various projects for individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) and their families.

Through Dr. Petrenko’s research projects, I provided direct support to children and adolescents with FASD through a skills group for children and the FASD Family Night Program. I have also spent a lot of time working with the caregivers of individuals with FASD as part of the Families Moving Forward Program; those caregivers own a special piece of my heart. Raising and loving an individual with a developmental disability is a very unique (and sometimes overwhelming) experience, but also such a rewarding one. Working directly with those caregivers has been one of the best parts of my training.

In addition to gaining clinical skills in individual and group therapy, I gained assessment skills in the FASD Diagnostic and Evaluation Clinic run by Dr. Petrenko. I seized the opportunity to administer various educational and neurodevelopmental assessments and learned the process of recognizing and diagnosing children and adolescents with FASD. At the University of Rochester, I also worked within the Department of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics (DBP) - that was led by Bryan's long-time mentor Dr. Tristram Smith - doing assessments for adolescents with autism.

During my time at Mt. Hope Family Center, I also assisted with Project STRONGER doing trauma-focused work with children, adolescents, and families. I provided both individual and family interventions with a trauma-informed lens with a focus on parent-child relationships. Working with family systems is very important to me, as I think that understanding the family as a whole allows me to better support each individual. Over the years, I have also spent time advocating and consulting with different schools in the area. I really enjoy collaborating with school teams to help them better understand and support individuals with diverse neurodevelopmental differences.

This fall (2019) I ran a group for adolescent boys with refugee status here in the United States. I was truly inspired by the resilience and joy I witnessed during my time with them. I enjoy group work with adolescents and I even spent a short time working on a project whose intervention included providing group yoga sessions as part of a social skills group. This meant I actually had to do the yoga with them, as part of their therapy, which the teens found hiliarious given my natural clumsiness and inflexibility.

I first met Bryan when he was completing his postd-octoral fellowship at DBP (which was super reassuring to witness someone that close to being finished with grad school!) and I was training within DBP's Behavioral Intervention for Families (BIFF) program with Dr. Laura Silverman. Bryan and I would eventually go on to do some more work together with assessments once his post-doc wrapped up as he began working in private practice.

And a little about me personally: I grew up in the Adirondacks and love spending time in the mountains visiting family and taking in the fresh air. Sitting by the water is my happy place; I am thrilled that my office is right on the Erie Canal with an excellent view! In my free time (which is currently pretty limited while I work on my dissertation), I like to read, spend time outside, and watch The Golden Girls. Once I finish my dissertation, I promise I will take up some more interesting hobbies!

I am so excited to be welcomed into Dr. Bryan Harrison's practice and am looking forward to working with individuals with developmental disabilities and their families. I am excited to begin using my beautiful new therapy chair, too. - Thank you, Bryan!